Why Africa Must Push Own Climate Agenda, Lead the Way at Cop-28

Posted by Mwangi Maina | Sep 4, 2023 | CLIMATE CHANGE, NEW FINANCIAL ORDER

As the Africa Climate Summit begins today, more and more people are focusing on the critical discussions that will shape the upcoming COP-28.

The continent of Africa is grappling with the harsh realities of climate change and the perceived unfairness it faces from global institutions.

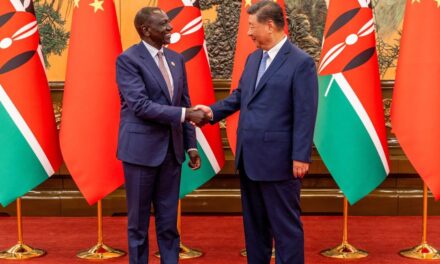

President Ruto, speaking recently in Nairobi, emphasized the need for collective action to find global climate solutions. He rightly called for reforms in multilateral financial institutions to make them more responsive to the needs of the Global South. Kenya, he noted, is not at the Paris climate summit to plead but to champion reform that enables developing nations to participate in climate solutions.

However, the central question remains: How can this be achieved?

The prevailing view in the lead-up to this Summit suggests that developing nations should assertively demand financial support from the wealthy Global North through existing International Financial Institutions such as the World Bank, Global Environmental Facility, IMF, and Green Climate Fund. There’s even talk of a global “carbon tax,” with the funds raised directed toward “green development” that would allow these countries to profit from “green energy” and minerals like cobalt and lithium on the global market.

However, skepticism arises. Can these very institutions, which have historically been criticized for contributing to poverty, indebtedness, and underdevelopment through structural adjustment programs, suddenly transform and work for equitable wealth distribution and development?

These institutions are still led and governed by individuals representing the old colonial powers. Is there a genuine possibility that they will change course and truly serve the common good?

Furthermore, we’re in the midst of a global economic and financial crisis. Europe is grappling with a cost-of-living crisis, while the US is weighed down by an escalating debt crisis, dimming prospects for economic recovery.

Seriously, can we expect meaningful change at this juncture?

A brief reflection on climate history is insightful. The UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was adopted in Rio in 1992. It introduced the concept of common but differentiated responsibilities (CBDR) and distinguished between developed and developing countries regarding legally binding emissions reduction obligations. This differentiation recognized the historical responsibility of developed countries for their emissions.

The goal of the UNFCCC was to stabilize global greenhouse gas emissions by 2000 at 1990 levels. However, this goal was never achieved. The US, Europe, and other Western nations continued to increase their emissions, while Russia impressively exceeded its reduction obligations by 30 percent.

Faced with their inability to meet their commitments, Western nations declared the UNFCCC’s goals insufficient and embarked on crafting the Kyoto Protocol in 1997. This treaty was more precise and ambitious, maintained differentiation between developed and developing nations, and reaffirmed CBDR. It allowed countries to exceed their obligations to sell surplus emissions to non-compliant nations, promoting global reductions without burdening less advanced economies.

But did it work? No. Developed countries soon realized they wouldn’t meet their commitments, and the US never ratified the Kyoto Protocol, persisting with emissions.

Russia, which again overachieved its goals, wasn’t permitted to sell its surplus reductions. Why? The EU deemed it excessive, undermining its achievements.

So, what did the EU and US demand? Predictably, they argued that the Kyoto Protocol lacked ambition and needed a more robust treaty, which they would unquestionably adhere to at this time.

This led to the Paris Agreement in 2015. While more ambitious, it abandoned CBDR, placing developing nations under similar obligations as developed ones. To balance this, the Green Climate Fund was established with much fanfare, aiming to raise $100 billion annually to aid developing countries.

But did it succeed? No. The US, under the Trump administration, withdrew for four years and continued emitting.

What about the Green Climate Fund? It exists but isn’t a significant funding source for the Global South. It relies on voluntary contributions, which the West often neglects. Compounding the issue, its application process is labyrinthine, forcing developing nations to spend additional resources hiring Western consultants just to apply. Outcomes are uncertain due to a lack of funds and political conditions.

What’s the West’s response? They demand more ambition. They insist on setting “net-zero emissions” targets, with the EU pledging to achieve it by 2030. Those refusing additional timelines face threats of trade barriers through Border Carbon Adjustment.

Remarkably, nations like Russia, India, China, Saudi Arabia, and others have proposed their “ambitious” timelines to avoid confrontations with the EU, showing their willingness to combat climate change.

Did this satisfy the EU and the US, which re-engaged with the agreement under Biden, asserting themselves as climate leaders?

No. They argue that other nations’ ambitions are neither credible nor ambitious enough. Such claims are difficult to challenge, as international organizations are controlled by individuals from the same countries.

What’s next? The EU and US will likely impose their Border Carbon Adjustment levy unilaterally, targeting those they dislike or fear as competitors, regardless of their actual climate efforts.

Looking at the broader picture, the history of the EU and US in climate efforts, even if they began with good intentions, raises doubts about their sincerity. The climate issue has become a tool to hinder the development of their competitors and maintain economic dominance.

Proposed solutions for developing nations often prove expensive, unstable, and ecologically uncertain. While renewables have merit, they are only suitable for specific situations, such as remote areas requiring electricity. Renewables alone cannot support industrialization due to their need for vast, stable energy sources.

Interestingly, hydropower and nuclear power, both GHG-emission-free, are criticized as “dirty” and “dangerous,” while the environmental costs of fracking for shale gas or massive wind farms are overlooked.

Hydropower, once established, offers free and stable energy for decades, reducing dependency on the West. However, nuclear power capacity resides mainly in Russia, China, and India, creating competition.

Given this context, is it reasonable to expect institutions that perpetuate underdevelopment to reform the global financial architecture and enable developing nations to partake in climate solutions? The analogy is akin to asking a thief to design an anti-theft system.

So, what can developing nations do to safeguard their interests in the global climate process?

Firstly, they must recognize that the existing global financial infrastructure primarily benefits the Global North, perpetuating the underdevelopment of the Global South. Limited and temporary responsiveness to developing nations’ needs is conceivable, but no permanent solution exists within the current IFIs.

While calls from Africa and other developing regions for increased climate assistance may yield slight increases in aid, it will likely come with numerous conditionalities. Furthermore, it will be tied to accepting Western “green” technologies that sustain dependence rather than fostering development.

Your support empowers us to deliver quality global journalism. Whether big or small, every contribution is valuable to our mission and readers.